Time Writer | Rainbow

Eat to live, but do not live to eat

In recent years, mainstream cinema has become more and more conservative, and the use of video by directors has entered a phase of no novelty.

Often times, we feel that a short, unobtrusive video is freer, more powerful and more aesthetically pleasing than a two-hour movie.

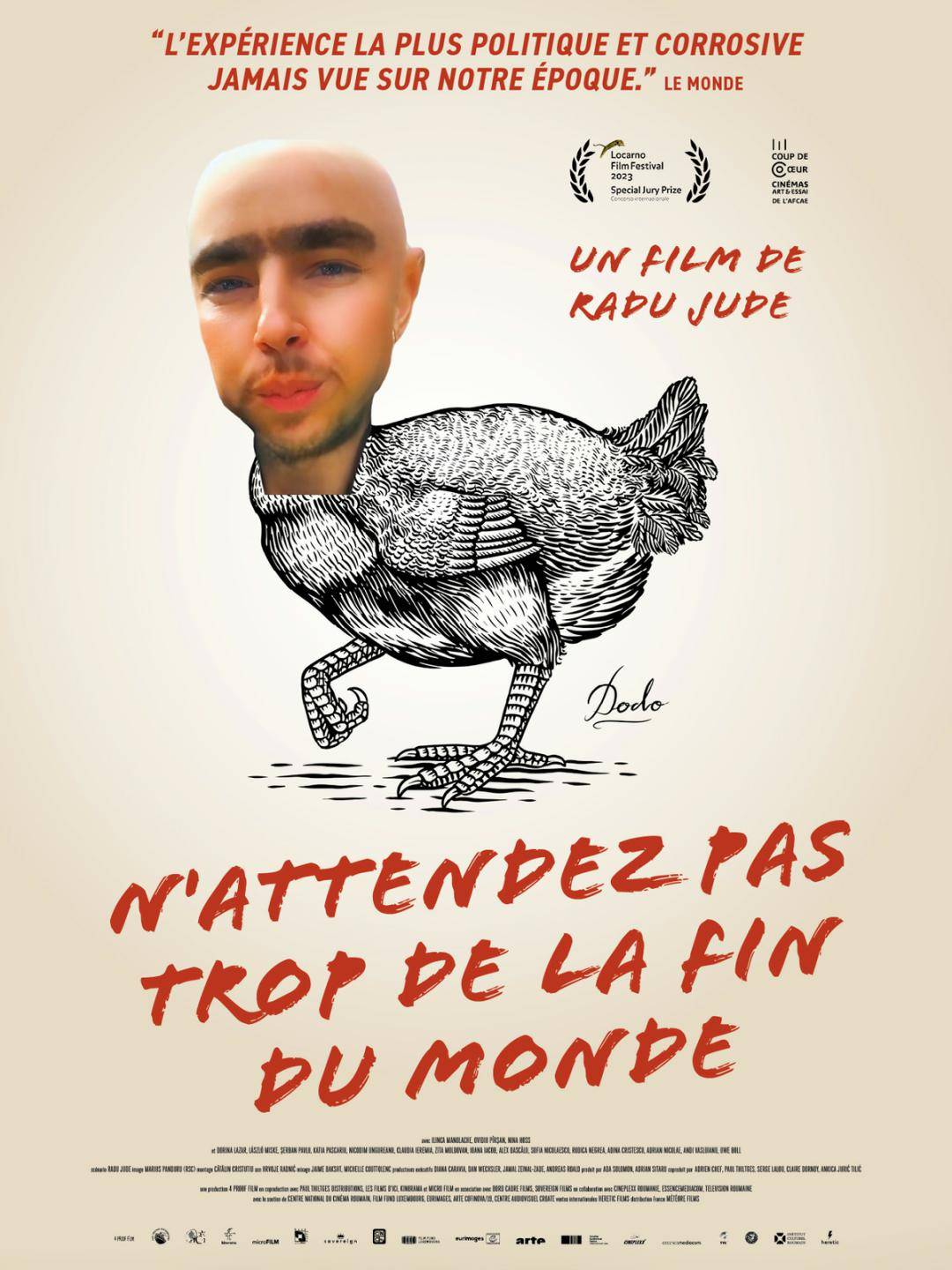

That’s why the emergence of Romanian director Radu Jude, who pioneered a style of cinema that is both jokey and serious, is so precious.

In 2021, Jude made a name for himself when he took home the Golden Bear at the 71st Berlin International Film Festival for Unlucky Sex, Crazy Porn.

In the last two years, when most people’s creativity has stagnated, Jude has gained a lot of inspiration.

Thus, in his new movie “Don’t Expect the End of the World” (hereinafter referred to as “End of the World”), the director uses the collage aesthetics to lead the audience to enjoy his unique expression once again.

Don’t Expect the End of the World Too Much

The main part of the movie tells the story of the heroine, Angela, who is overworked.

This issue of labor in the era of neoliberal zero-work economy has been a hot topic in recent years, as British director Ken Loach’s Sorry We Missed You (2019), for example, also attempted to explore.

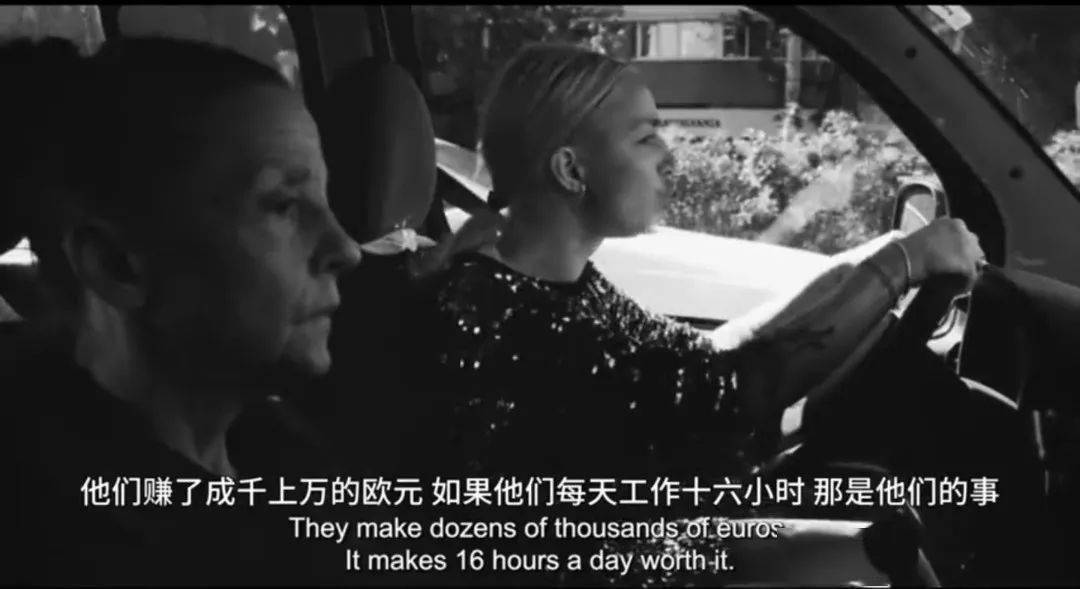

The story of Armageddon stems from Jude’s personal experience of working as a production assistant years ago, and the heroine, Angela, who is also a production assistant and spends basically 24 hours in her car, even including sleeping and sex.

The project she was in charge of had to do with a work-safe short film shoot that required driving around the city of Bucharest.

She had to find four short film protagonists to be cast in one day, shoot audition clips for them, send them to the Germans and Austrians to make a decision – and finally return to the office for a meeting at five in the afternoon.

Jude’s ambition is clear in his seemingly documentary style: he wants to make the images themselves radical to reveal social issues.

Angela usually wakes up at five or so to work, more miserable than a 996 hitman.

When she arrived at the first auditioner’s house, the person was out fishing and had to record via Zoom video.

This process involved Angela getting the male across the room to change the background of the video and turn his bandaged hand to the camera so it looked a little more miserable.

In other words, it’s more in line with the stereotype of happy white people from capitalist countries.

It wasn’t so much that Angela discriminated against others, but that she knew the rules of the operation so well that she was even able to make a mockery of them at her fingertips.

Only when she is with her mother does Angela reveal the hardships of her job.

Working sixteen hours a day on a project is common; so is hitting the German director when he gets cranky; and she even fell asleep last night driving her car and was finally awakened by the honking of the horn behind her.

It’s ironic isn’t it, that Angela is working on a short film that promotes work safety when her job is capable of killing her at any time – it’s only a matter of time before she either dies suddenly or gets into a car accident.

Up until here, “Doomsday” has presented all of this in a sort of documentary style, not exaggerated or rendered, but incredibly real.

When Angela tells her boss that she could die of overwork at any moment, the opposite side of the table says it’s a problem that can be solved with a cup of espresso, and then proceeds to talk about how hard she works too.

But Angela privately spits out that if you work 20 hours to make $20 million that’s your business, but I work 20 hours and beg for your paychecks – isn’t that what goes through our minds when we complain?

Not to mention all the problems that the movie brings out: corruption, the aftermath of dictatorships, the government and corporations at odds resulting in uncollected garbage from apartments, beggars on the street everywhere, drivers and pedestrians on the road blowing up at the slightest point ……

When Angela is overworked, her cell phone always rings with the familiar ringtone of Ode to Joy. But, we all know there is no joy to be found in her life and the world around her.

It’s worth noting that the movie’s title, “Don’t Expect the End of the World,” is taken from the Polish-Jewish poet Stanislaw Reich, who famously said, “When an avalanche comes, not a single snowflake feels responsible for it.

In this movie, Jude is undoubtedly using this cold humor to present his attitude: compared with the end of the world, is not the present moment more desperate?

We’ve already reached the future we’ve been waiting for in the past, and it’s even worse, so who knows if the end of the world isn’t the pinnacle of misery?

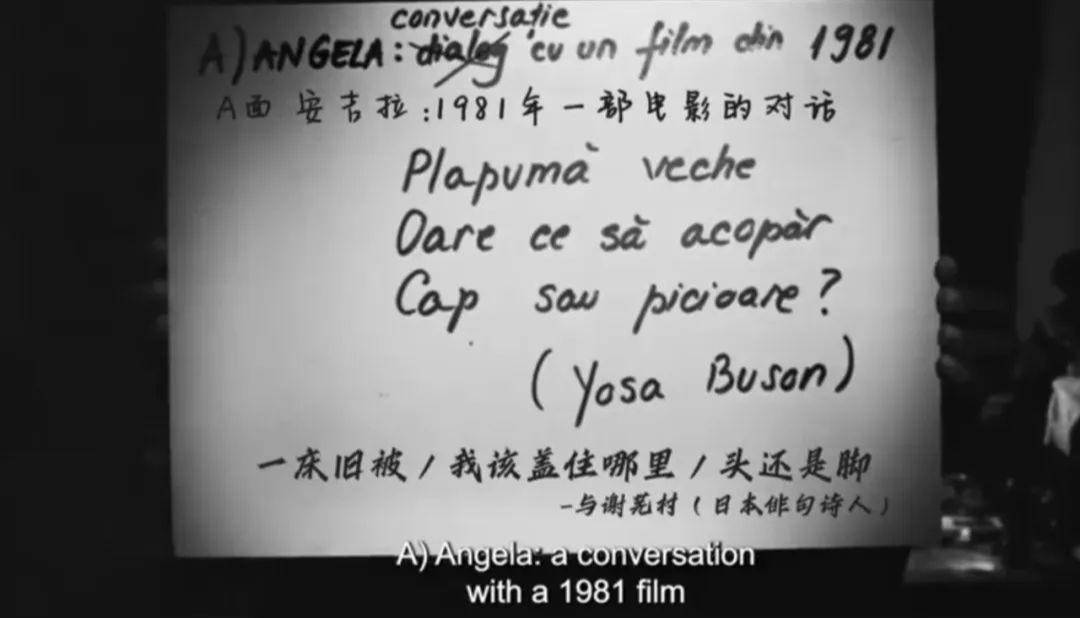

Parallel to Angela’s life in the present is footage from Lucian Bratu’s 1981 color feature film, Angela Who Goes On.

This is a Romanian film, made during the socialist period under Nicolae Ceausescu, about the life of Angela, a female cab driver.

When similar footage from the two movies is edited together and compared, we get the distinct impression that the times don’t seem to have done much for the general public.

Even, like the sharp contrast on the screen, the life of Angela in the 80’s counts in color and modern Angela is all black and white.

While the former can still have a relationship and a private life in between driving a cab, the latter can only deal with her private life in between working.

Angela works in the car, meets with her mother in the car, takes a couple sips of a functional drink when she can’t stay up, plays the radio loudly, swipes through Tiktok for a while, and squints for a couple minutes if she can’t be bothered.

Unlike ordinary road movies that are an escape from everyday life, Angela’s life in the car is purely quantified by capital.

The Romanians represented by Angela – or rather the community that acts as a labor market – actually serve around the always absent first capitalist state.

The Austrians and Germans in the film, for example, as well as the Americans, who are never present but invariably absent.

In post-capitalist Romania, the invasion of American culture becomes a blatant presence.

For example, the slogan “We’ll send you to America” appears at the beginning of the movie, and the Trump Tower in Las Vegas is in the background of the Zoom videoconference.

In the juxtaposition of images, the romanticism of Angela Goes On takes on a starkly ideological tone.

The stifling and maddening social environment is intensifying at this moment, and Bucharest today looks even worse than it did in the past.

In this setting, Jude was inspired by the Soviet film theorist and filmmaker Eisenstein’s idea of having two sets of images clash.

At this point, contemporary Angela’s life is an advanced version of Angela’s life in 1981, and the truth.

This revelation is the power of images and Jude’s embodiment and use of their radical creativity.

Finally, in finding the last auditioner, the two Angelas magically meet: the grandmother in that home is the same Angela who drove a cab in 1981.

At this point, the border between the real and the virtual breaks down, and Doomsday enters a moment that is uniquely cinematic: the years 1981 and 2022 are reunited, and at the same time both become truths about each other.

It turns out that what appears to be freedom is actually another kind of totalitarianism, and that the movies shaped under totalitarianism will be subverted by the movies of forty years later.

While Angela’s family in 1981 is finally chosen by the company to be the protagonists of the short film, Ovidiu, the injured worker who left the country, is constantly humiliated: he cannot mention Russia, he cannot mention overtime, he cannot say that the company is wrong, and he can only say that he is paralyzed because he did not wear a helmet.

The Ovidiu family complains, but the 1,000 euros a day is too much, so they can only silently hold up the green board that can be photoshopped with anything.

In a roundabout way, it turns out that slavery just exists in a different way now.

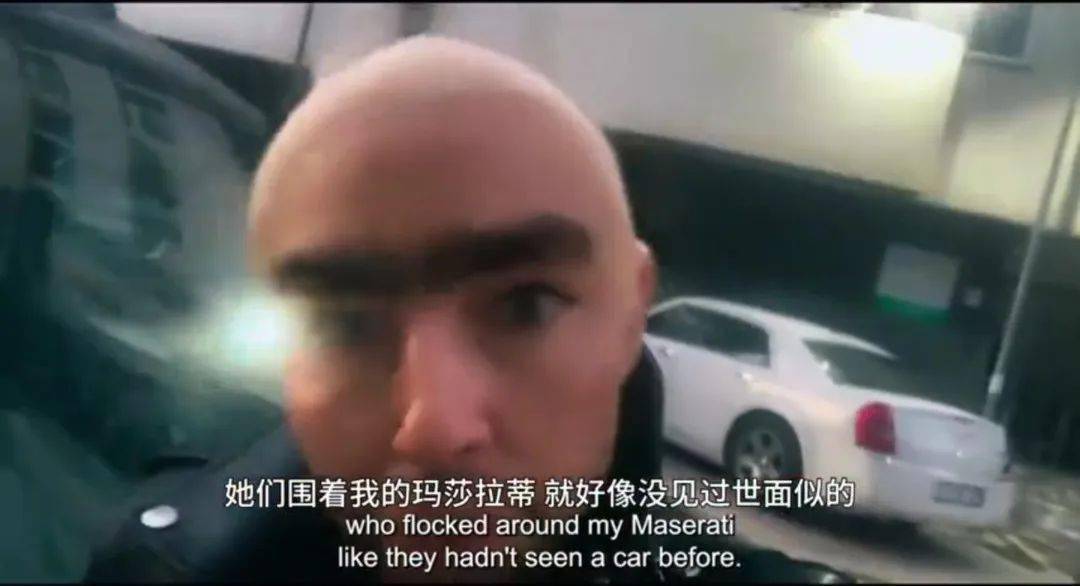

The most interesting setup in Armageddon is Angela’s penchant for employing filters on TikTok to relieve the immense pressure of her job, pretending to be Andrew Tate (an internet celebrity who was arrested for human trafficking in Romania in 2022), and posting a lot of misogynistic, gold-digging, and other vulgar comments.

If we only looked at Angela’s online statements, we would undoubtedly be able to conclude at a glance that there is something wrong with the person, and probably a report would be at hand.

But in real life, Angela is actually the complete opposite of the video.

She is young and beautiful, hard-working, funny and humorous, paragraph allusions open mouth; humble and courteous to people, kind and generous, will give HOMELESS money, but also to help the auditioner to better get the job; she even reads books in her spare time are “Remembering the Watery Years” ……

The great tension inherent in the online world is brought out in this stark contrast.

Jude uses a variety of images at his fingertips in Armageddon: old movies, silent films, still images, short videos, and so on.

But it’s not the future of cinema he’s predicting, but the subversive nature of the image that short video carries within itself.

For the pro-capital medium of film, it’s like a gun that allows images to multiply in huge numbers while digging their own graves with their own hands.

If everyone can pick up a cell phone and shoot, if people dance with the medium in a gesture of curiosity, then exposing the truth becomes an end that is not an end in itself.

And so Jude’s movie becomes a parody, and a revolution, in itself.

The value of the revolution itself lies not in the revolutionary gesture, but in the uncontrollable drive.

There is no need to straddle the gap between truth and fiction; the truth is contained within the gap between truth and fiction.

However, there is a certain threshold required to watch Armageddon, and viewers would do well to have a grasp of the juxtaposition of film and history. Otherwise, it’s easy to understand the movie and either get caught up in the form itself or go against the director’s delivery.

-END-

Previous Picks Review.

Top 10 Anticipated Movies of 2024, are there any you want to see?

Nicolas Cage, finally breaking the curse of bad movies